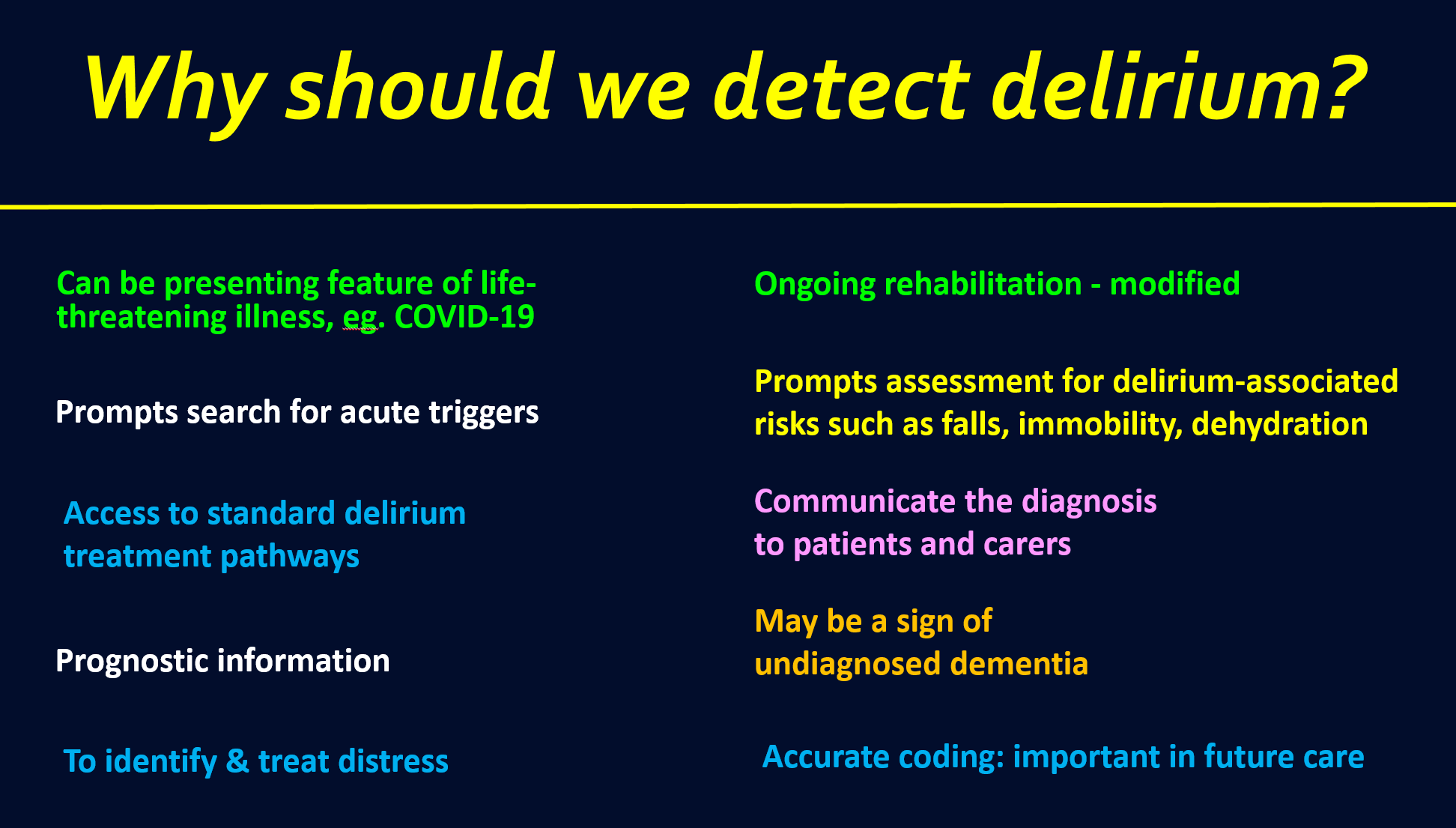

10 reasons why we should detect delirium

[1] Delirium can be a presenting feature of life-threatening illness, physiological disturbance or drug intoxication

People with delirium often have serious, acute illness. In some cases the delirium is the presenting feature, with perhaps only a few other clues. These clues might be a lower blood pressure than expected, or borderline low oxygen saturations. It is also common to see major physiological disturbance in delirium, for example hypercapnia or low blood glucose. Drug intoxication, often with opioids, is another serious cause of delirium that requires prompt action.

It is frequently seen in practice that a person with delirium superimposed on dementia does not receive a proper diagnosis of delirium. Instead, a vague term like ‘confusion’ is used not as a starting point, but as a conclusion.

It also still happens that even without a prior diagnosis of dementia that delirium is mislabeled as ‘confusion’ or some other non-diagnostic term.

The problem with this is that these terms do not convey the acute and serious nature of delirium. When delirium is diagnosed this should trigger first an urgent evaluation for acute, life-threatening illness and/or physiological disturbance, and drug intoxication.

The word delirium implies ‘emergency’, ‘acute’, ‘urgent’, ‘hazard’, and so on. Much more than ‘confusion’.

The word ‘delirium’ compels action.

[2] A delirium diagnosis prompts a systematic search for triggers

Following the initial assessment for life-threatening illness, it is necessary to conduct a more detailed search for possible causes and factors that might be exacerbating the delirium.

We know from studies that there is often more than one cause of a person’s delirium (Laurila et al., 2008). Good practice therefore should involve a systematic search for possible triggers.

In my own practice this would involve considering different organ systems, physiological changes, drugs, environmental changes, and so on.

[3] A delirium diagnosis provides access to standard treatment pathways

Many hospitals now have delirium treatment pathways. Here is one from the Scottish Delirium Association that has been adopted by many hospitals.

The use of the term ‘delirium’ instead of vaguer terms makes it more likely that the patient will undergo a more formal work-up, guided by an established treatment pathway.

There are no pathways for ‘stupor’, ‘obtundation’, or most other less well-defined clinical terms that often indicate delirium. There are pathways for ‘acute encephalopathy’ but on a google search they mostly appear to be specific to presumed cause, and so are not as broad or deep as delirium pathways.

[4] A delirium diagnosis provides prognostic information

Delirium is associated with a high mortality. Several studies show this, with some showing an independent effect of delirium (Salluh et al., 2015). Additionally, acutely reduced level of arousal, which in patients without coma is strongly indicative of delirium, is also associated with high mortality (Todd et al., 2017).

Cause and effect is not clear, as delirium is also linked to vulnerability factors like frailty. However, either way it is a strong indicator of mortality.

Delirium also predicts many other adverse outcomes such as prolonged hospital stay, and new institutionalisation.

Naturally it is very important that patients and families are aware that delirium increases the risk of poor outcomes.

Persistent delirium

There is also the key issue of persistent delirium. Around 20% of delirium persists. Sometimes there is partial recovery, but either way the outcomes are poor. When a person has delirium for more than 5 days - one definition of persistent delirium - it is even more important to keep families informed about the risk that the patient may not do well.

[5] A delirium diagnosis prompts a proactive assessment for distress

People with delirium are often distressed (Partridge et al, 2020). When a person with delirium is expressing fear through their words, and especially when they are obviously agitated, it is not difficult to detect this distress.

But more challenging is when a person is not spontaneously speaking of their fears. Importantly, people with hypoactive or mixed delirium may have distressing psychosis but may not express this.

I have learned in my own practice to ask patients specifically about fears or concerns, and explicitly to ask about hallucinations. These questions often yield a positive response.

There are several other causes of distress, both physical and psychological. These include pain, acute urinary retention, thirst, and a feeling of disorientation. But you can’t efficiently pick these up and address them without first detecting distress.

Good practice in delirium assessment involves multiple actions. One of these is the proactive assessment of distress.

[6] A diagnosis of delirium modifies rehabilitation but not should not halt it

Previously it was often seen that any form of delirium would mean that mobilisation and other forms of rehabilitation would just stop. Thankfully practice is changing such that instead of simply halting rehabilitation, a modified approach is used.

In a person with delirium, the rehabilitation needs might be related to a different problem, such as hip fracture or stroke, but also involve rehabilitation of the delirium itself.

For example, in starting the rehabilitation session with a person with delirium the nurse or therapist may initially try to engage the hypoactive patient in conversation, even if this is simple. The nurse or therapist should encourage and facilitate mobilisation as able, possibly doing passive range-of-movement exercises. Relatives can also be involved, providing cognitive engagement, help with eating, and so on. Attempting these kinds of interactions is likely to more be more effective than doing nothing.

Rehabilitation of delirium itself is under-researched but many experts believe that rehabilitative measures including cognitive engagement, mobilising, encouraging normal activities as much as possible, and so on, are valuable in helping a person recover.

More formal approaches are emerging - for example in this interesting paper.

[7] A delirium diagnosis prompts assessment for delirium-associated risks such as falls, immobility, and dehydration

Delirium is a risky condition. As well as being linked with mortality, it is also linked with several other complications. One of the most prominent and potentially of these harmful is falls.

Other risks include dehydration, malnourishment, lack of mobilisation, deconditioning, pressure sores, aspiration pneumonia, leaving the ward and becoming lost, and non-compliance with drug or fluid administration leading to inadequate care.

With a delirium diagnosis, the vulnerability of the patient is highlighted to the multidisciplinary team. This enables the team to take steps to reduce the chance that one of the many complications of delirium occurs and leads to significant harm.

[8] A delirium diagnosis allows accurate communication with patients and their families

One of the saddest and most avoidable consequences of delirium is when the patient and family do not understand what they are going through.

Numerous reports now show us that this lack of clarity causes considerable suffering.

For some people an episode of delirium can be one of the worst experiences of their life. Similarly, observing a family member becoming terrified and psychotic can be extremely distressing for families.

A formal diagnosis of delirium facilitates a clear discussion with the patient and their family. Experienced clinicians know that simple provision of the diagnosis along with, perhaps, a written booklet, can make an enormous difference.

See here for a blog on this topic which has some links on useful sources of information for patients and families.

[9] In older people, delirium can be a marker of undiagnosed dementia

Dementia is very common in acute hospitals: approximately 1 in 5 people in a typical general hospital will have the condition (Jackson et al., 2017). Dementia remains underdiagnosed; the best-performing countries diagnose and manage 70% of dementia. In many countries the rates of formal dementia diagnosis are much lower.

With these numbers it is clear that large numbers of people with undiagnosed dementia are being admitted to hospital.

Some studies show that more than half of hospitalised older people with delirium also have dementia.

So this means that a hospitalised person with delirium with no prior diagnosis of dementia has a very good chance of having dementia.

What should we do about this?

Formal dementia diagnosis is challenging in the hospital context because in the presence of delirium cognitive tests are not informative. Additionally, even if you want until the delirium has resolved, the person may not perform at their baseline level. There are lots of reasons for this including sleep deprivation, drug effects, stress, the testing environment, and possibly the after-effects of delirium (which may be long-lasting though not always permanent).

However, there is useful research showing that informant tests such as the Informant Questionnaire for Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) can provide useful information even during an episode of delirium. Additionally, a standard informant history concerning a person’s level of function before the episode of delirium may give useful clues.

Formal diagnosis of dementia in hospitalised patients remains relatively uncommon, though in patients with long admissions and a good source of informant history it is done. For the majority though, when delirium is diagnosed an informant history, perhaps augmented by a formal scale like the IQCODE, may yield information that suggests dementia. Depending on the circumstances this may then lead to appropriate follow-up, for example through the general practitioner or community-based mental health services.

Delirium in a hospitalised older patient with no known dementia should prompt the question: could this person have dementia?

[10] Accurate coding

Finally - isn’t it odd that we are so inconsistent in recording ‘delirium’ in medical records? A condition that affects at least in 1 in 7 hospitalised patients shows up as a tiny fraction of that in the records.

The two main reasons for this are likely the lack of detection in general, and the inconsistent use of terminology.

This matters from the point of the patient, because a history of delirium means that the person is more likely to develop delirium in the future. Personally I find it helpful to know if there has been a previous episode of delirium when I am seeing patient, because this allows for stepping up preventive measures and our monitoring for new delirium. It also prompts me to ask them if they remember having delirium and to talk about the risk of getting it again. It can be reassuring to a patient to know that their doctor or nurse knows about delirium and will take steps to help them avoid it, or to recognise and treat it early if it occurs.

It is also important from the perspective of the provision of care at a systems level. The invisibility of delirium in coding terms no doubt has had an effect on planning of services. Its disproportionately low profile means that resources such as specialist nurses and systems of care that might reduce the risk of delirium are less likely to be deployed.

There is also an implication for research as we move into a time with more and more large scale research using routine healthcare data. The lack of accurate coding of delirium will severely hamper our use of these powerful new methods.

So there we have it - 10 good reasons to detect and document delirium. Hopefully we will see increasing use of the term and all the attendant benefits.

References

Jackson TA, Gladman JR, Harwood RH, et al. Challenges and opportunities in understanding dementia and delirium in the acute hospital. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002247. Published 2017 Mar 14. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002247

Laurila JV, Laakkonen ML, Tilvis RS, Pitkala KH. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in a frail geriatric population [published correction appears in J Psychosom Res. 2008 Nov;65(5):507. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.05.026

Salluh JI, Wang H, Schneider EB, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 2017, 350, h2538. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2538

Todd, A., Blackley, S., Burton, J. K., Stott, D. J., Ely, E. W., Tieges, Z., MacLullich, A., & Shenkin, S. D. (2017). Reduced level of arousal and increased mortality in adult acute medical admissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0661-7

Williams, S. T., Dhesi, J. K., & Partridge, J. (2020). Distress in delirium: causes, assessment and management. European geriatric medicine, 11(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00276-z